>>> For the German version of this article please click here <<<

In her 2018 stand-up special Nanette Hannah Gadsby talked about things that were unheard of: Self-deprecating comedy is flawed. It doesn’t suspend the humiliation, it freezes it, Gadsby said. As a lesbian woman, she thus makes herself an accomplice to her own oppression. Therefore, in Nanette she announced her withdrawal from comedy.

Many, including myself, thought this was an earthquake. Comedy would never be the same, Nanette was the special that ended specials. „The best comedy program ever,“ German weekly DIE ZEIT called it. And even if you disagree, you can acknowledge this figurative mic drop of ending a career on stage.

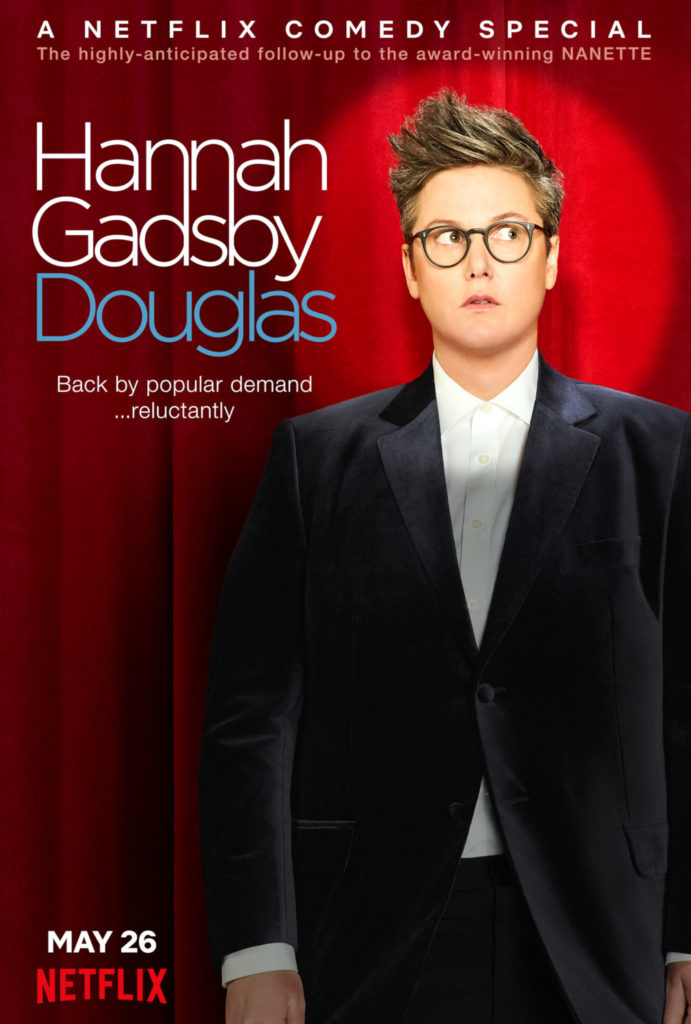

But Gadsby went on. Douglas is her tenth special, the second on Netflix. The announcement left me wondering: How is this supposed to work? Isn’t this the destruction of everything she carefully built with Nanette?

The short answer: no, Douglas doesn’t refute anything. But, of course, it can’t compete with its predecessor. Comically speaking, Douglas is a mediocre stand-up special. But it is significant nonetheless, because it is greater than its comedy.

So first to the comedy: Gadsby begins Douglas with a summary of Douglas. Since no one knows what to expect from her after Nanette, she says, she simply announces all segments of the show in advance: observational jokes, which she says are not very good, art historical digressions, bait for her haters. She will talk about her autism diagnosis and about vaccination opponents. And she will tell the audience when they will find something funny, and also: when they will find something funny, because they will remember Gadsby’s explanation from the beginning of the show. And then again („I added a third layer to your humor cake“) when the audience would remember these laugh predictions.

Much meta in „Douglas“ remains an end in itself

This shows how impressively thought-out and sophisticated Gadsby has designed Douglas. And it’s also impressive how well she acts it out. However: What’s the use of the most beautiful meta-construction if the predictions are not fulfilled and as a result, as happened to me, do not yield laughter?

If Gadsby knows that jokes about different expressions in US and Australian English are bad (or those about golfers or about the paleo diet), and then makes those jokes, it doesn’t help. They are still bad jokes.

In the „Good One“ podcast Hannah Gadsby explained that she had constructed Douglas like a musical fugue. In other words: polyphonic and with recurring motifs. I’d say also with a lot of pleasure in language and playing around with words. That’s nice, but at times it gets a bit tiring. Many callbacks remain a pure end in themselves.

Or fizzle out completely. An example: The pouch of Douglas (an „extension of the peritoneal cavity“ in the female body that serves no survival purpose) serves Gadsby as an example of patriarchal naming mania and an occasion for wonderful rants. While walking her dog Douglas, she explains to a stranger in the park that she allegedly named the dog after the pouch and what this cavity in the female body is all about. To prove how absurd her thinking is, Gadsby keeps coming back to this episode. However, one has heard more absurd stories, especially in comedy specials. As proof of absurdity this one is only of limited value, insisting on it seems powerless and irritating.

More articles in English

A small selection of articles at Setup/Punchline is also available in English. <br>Find out more.

It wouldn’t even be necessary, because Gadsby has great material and it wouldn’t have hurt Douglas either to have it cut by fifteen minutes. (Gadsby arrives at the dog episode after 23 minutes, after the initial summary and the hacky observational jokes. So, a third of the special is already over by then.) Her art history lectures are full of drive and are among the best of the evening. You really have to have an eye for curiosities in the paintings of the so-called old masters, such as cats with strokes or strangely slipped fabrics. („Thank god you’re in the nude, because I’m painting a landscape!“)

It’s also great fun how she combines art history with the Heroe Turtles or re-identifies „Where’s Waldo“-Waldo as a typically ignorant idiot man. Or that confusing experience from her school days, which she can only explain in retrospect with her autism diagnosis.

Of course: Such highs are not conceivable without lows. But when the lows are then, for example, „Who goes in which Hogwarts house“ jokes, it’s a little disappointing. 23 years after the first Harry Potter novel was published, this joke field lies idle.

Hannah Gadsby can’t dissolve her message into comedy

With her „needling of the patriarchy“ Gadsby kicks at open doors with her fans. There’s nothing to be said against it: She’s right and she formulates wonderfully detailed. It’s just not particularly funny. If a joke is funny because it surprises and amazes, it can’t be very funny in the end where, instead of creating surprise, it meets expectations.

That doesn’t make Gadsby’s message wrong, quite the contrary. It is too big, too true: It simply cannot be dissolved in comedy alone. You would need one more thing to do that. For example a heightened stupid attitude, like when Michael Che, in Michael Che Matters (2016), seems to be engaged in a serious bargain about the slogan „Black Lives Matter“. Or a tender refraction, like when Michelle Wolf, in Joke Show (2019), as woke feminist also has some uncomfortable remarks for woke feminists. Gadsby has force, anger, energy and belligerence. That’s a good deal more, but not a funny one.

But enough with the comic criticism, because it doesn’t do justice to Douglas anyway. In the end, it is also a dispute with the haters and Gadsby is enjoying it.

The symbolic order of the world is created by men, and Douglas deals with this to a large extent: Dr Douglas names his pouch, Pythagoras names his triangles, men call Gadsby’s specials „no comedy“. If she would try to make it especially difficult for these critics (or rather: haters) by making the best possible jokes, Gadsby would again make herself dependent on the naming and evaluation authority of men. And because the world can accuse women of everything, and I mean: everything („one woman show“), reasons would soon be found again why Gadsby’s jokes are still bad after all.

If, on the other hand, she announces that she is about to make bad jokes, she retains the initiative: She judges the jokes before anyone else and even the haters have to agree with her. And while they’re at it, they will, of course, also call all her patriarchy jokes bad and boring. And, by doing so, they will also confirm that the premises of these jokes, that are hostility towards women and queers, are also long known and worn out. To force haters to admit, albeit implicitly, that they have no better reasons for their hatred than queer and misogynistic attitudes, is a feat and in the end, perhaps, the best joke of all.

Setup/Punchline – The Comedy Newsletter

News, articles, interviews, podcast and series recommendations about stand-up, comedy and humour in general. Biweekly via mail. >>> Subscribe <<<