Behind every successful comedian in the US are fifty that nobody knows. They don’t perform in New York or Los Angeles, but in cities with names like Boise, Spokane or Tucumcari; not on late-night shows on national TV, but on cruise ships, fairs and bachelor parties. They are on stage a good 200 days a year. Because they want to, of course, but also because they have to: to somehow break even.

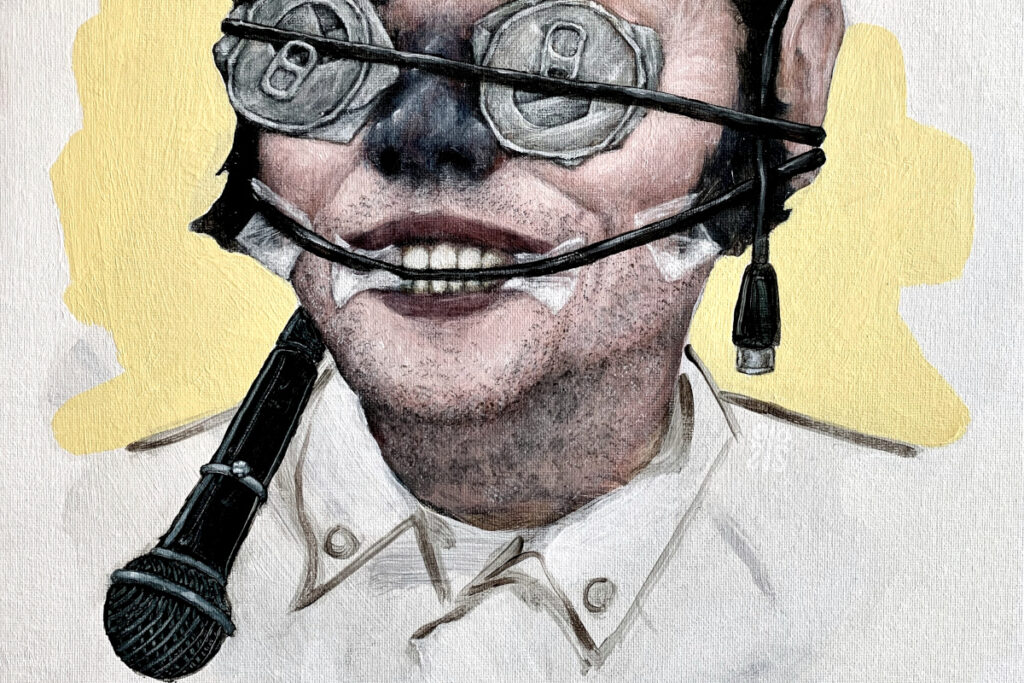

Stand-up comedy is not only glamorous, funny, and, at times, philsophical. Stand-up is also a sinister mine. And one of the darkest workers in it might be Billy Ray Schafer. He is the main character of Running the Light, probably the first and so far only novel from the world of stand-up comedy, published in spring 2020.

With the character Schafer, the author, the US comedian Sam Tallent, has created a monument to the type of the road comic: Schafer is a washed-up artist in his early 50s who plays the dense network of comedy clubs in the provinces, lives out of a suitcase, sometimes hooks up with a groupie and otherwise destroys himself with alcohol, cigarettes, cocaine and fast food.

It wasn’t always like this. In the outgoing comedy boom of the 1980s, Schafer was a promising newcomer: he appeared on Johnny Carson’s and David Letterman’s shows, taped a special, had a writing job in Los Angeles. Then he crashed: divorce, neglected children, drug swamp. In a mixture of Kerouac and Bukowski, but with humour, Tallent tells how Schafer struggles with himself during seven days of road life and hopes, as a repentant sinner, to start over again. Does he succeed or does he push his luck? The title also alludes to this: „Running the light“ is stand-up jargon for overstaying your allotted playing time on stage. So what about Schafer? Is he already over his time?

Clever concept, sometimes overdone

First of all, he is a comedian who stands between all these worlds: he once had almost everything, now there is almost nothing left. Schafer is neither part of the first nor the second comedy boom. He doesn’t belong to any group.

This is a clever conceptual decision: On the character level, it allows Tallent to portray Schafer as a cantankerous outsider, all leather, sweat, instinct and violence, who would prefer to spend the night with the snakes in the open air, far from any civilisation. And on a more abstract level, Schafer becomes a prism in which discourses and developments about stand-up are condensed.

„[Nathan] said he was pleased to meet Billy Ray, that he’d heard his name on podcasts, and Billy Ray asked ‚What’s a podcast?‘ and Nathan and Kevin laughed in deference and Billy Ray, unsure, acted like he was joking.“

Such passages are delicious, but too often also exaggerated in their explicitness. All in all, despite the smoke, dirt and blood, it all seems very much like a clinical and experimental setup. The characters seem a little too typecast, the dialogue generic. As if not people but concepts, ideas, convictions were talking to each other.

Running the Light: A novel about yesterday-ness

The aforementioned clash with the next generation of comedians is a good inside joke for comedians and fans. Narratively it serves no purpose, it doesn’t arise out of any inner necessity of the story. It falls flat as an expose of Billy Ray’s stiffness, which wouldn’t be a bad thing if it weren’t one of dozens of evidences of the protagonist’s stiffness in a novel about stiffness, and the struggling with that stiffness by a really extremely stiff character who is out of time.

Somewhat redundantly, masculinity markers are also used. Schafer is endowed with an antiquated ideal of masculinity that nowadays would be described as toxic. The manifestations of this ideal are, of course, well known to readers. Tallent unfortunately does not add any new perspectives on the phenomenon, no new words or images in which to clothe this masculinity. It may be that there is no other way: How else should one depict toxic masculinity? But it could also be that the novel itself radiates some toxic masculinity; the boundaries are not always entirely clear. In any case, some passages are so dripping with Schafer’s desperate masculinity that it becomes unintentionally funny:

„Before he took a shower, he masturbated into the sink with the lights off so as not to see himself in the mirror.“

Who’s to blame for the messed up comedian’s life?

It’s like stand-up: making friends laugh doesn’t make a comedian. And a string of anecdotes, oneliners, stand-up sets, thoughts and insights about the nature of comedians does not necessarily make a good novel. Of course: the anecdotes are witty, the oneliners cool, the sets impressively intuitive and the thoughts about comedians‘ instincts interesting and accurate. It is on the story level on which Running the Light lags behind. But if you’re looking for exactly those anecdotes and insights, Running the Light is your best bet.

And to dissect the discourses and developments in stand-up, the novel has plenty to offer. One question in particular, which is rarely asked, shines above all in Running the Light: Who is to blame for this messed-up comedian’s life?

Is it really Billy Ray Schafer, who made bad decisions, destroyed his private life and his career? Or is there more to it? What role does the entertainment machinery play in all this that sucks in aspiring artists, squeezes them out, spits them out and leaves them by the wayside? Of course and luckily, Tallent doesn’t provide an answer, but the fact that the question always resonates is a great merit.

„Of his many titles, more than husband, father, homeowner or sane, it was most important to Billy Ray that he be defined as a comedian, and a good comedian at that.“

The Chicago Reader, on the other hand, has found an answer. In an article it says, optimistically: „It’s for the best that Billy Ray represents a dying species.“ Unfortunately, this is not true: Running the Light is not the story of an anomaly that finds no place in the wheelwork. It is a story about an anomaly created by this exact wheelwork. Billy Ray Schafer is a surrogate, representing hundreds or thousands more. The system needs them. Behind every successful comedian are fifty that nobody knows.

Who knows, today’s Billy Ray maybe he doesn’t do so much coke or drink so much anymore. Maybe he doesn’t look for constant fights and beatings, maybe he doesn’t make homophobic jokes any more. But this type is not extinct. Billy Ray Schafer is pretty much alive.